Researchers

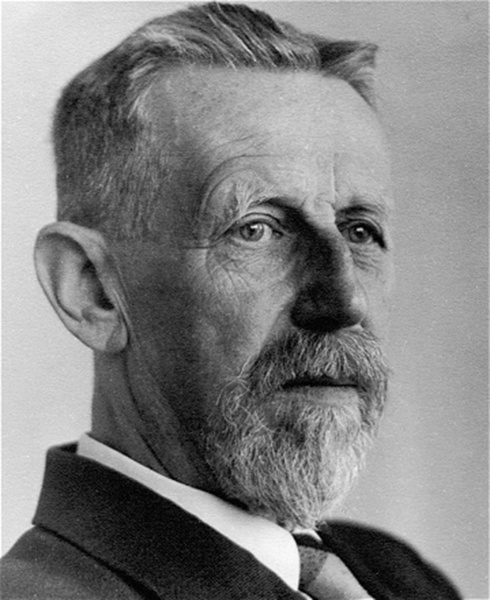

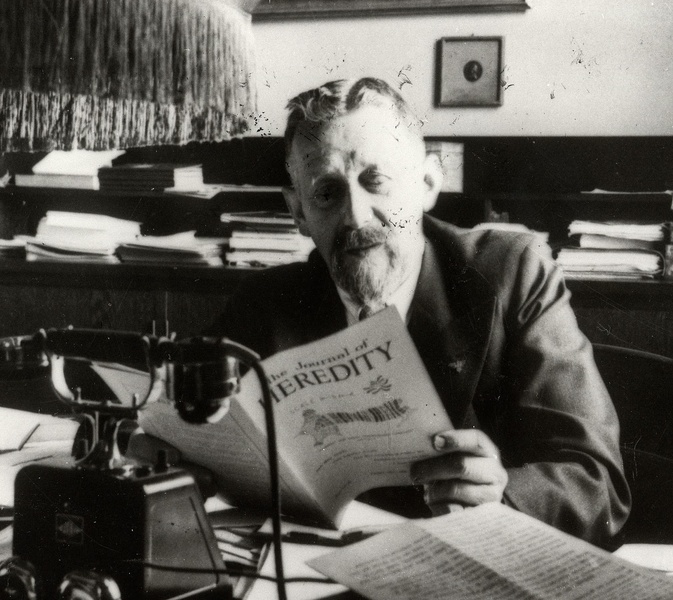

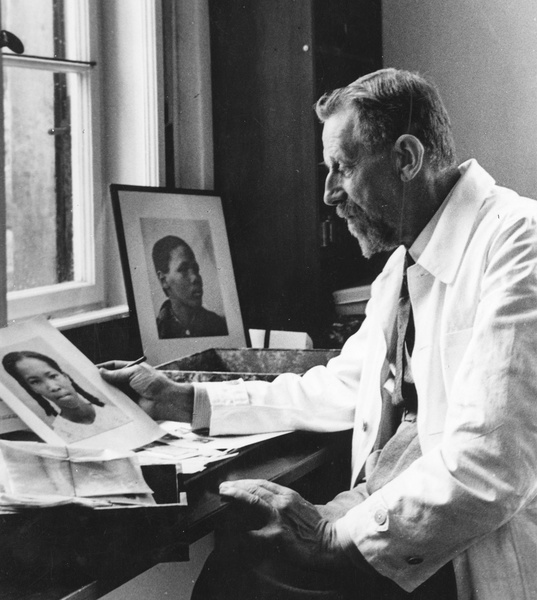

Eugen Fischer

(1874-1967)

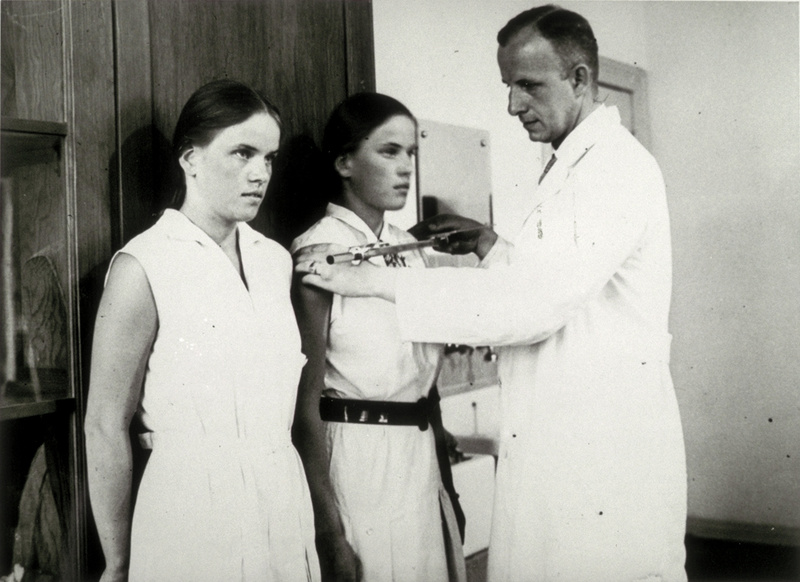

Anthropologist and Anatomist

Director of the KWI-A (1927-1942)

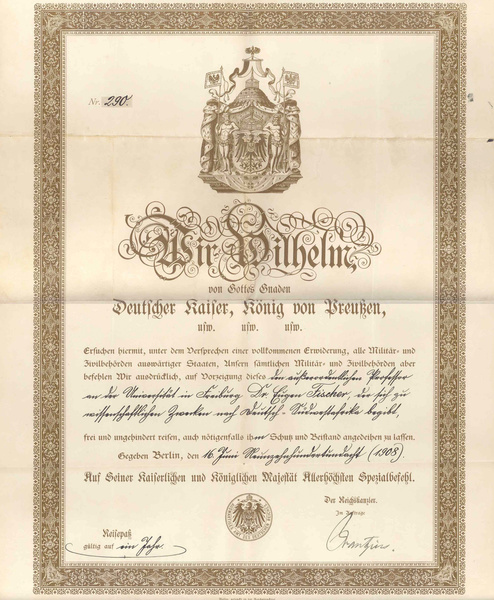

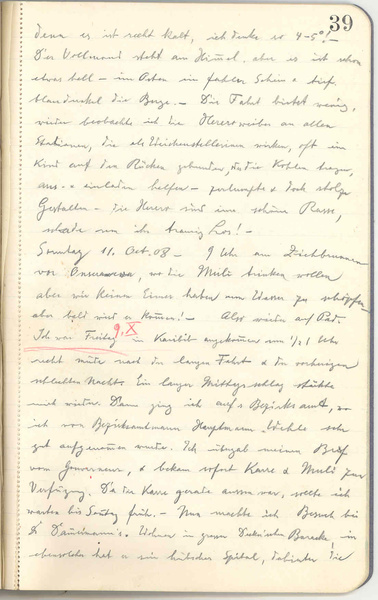

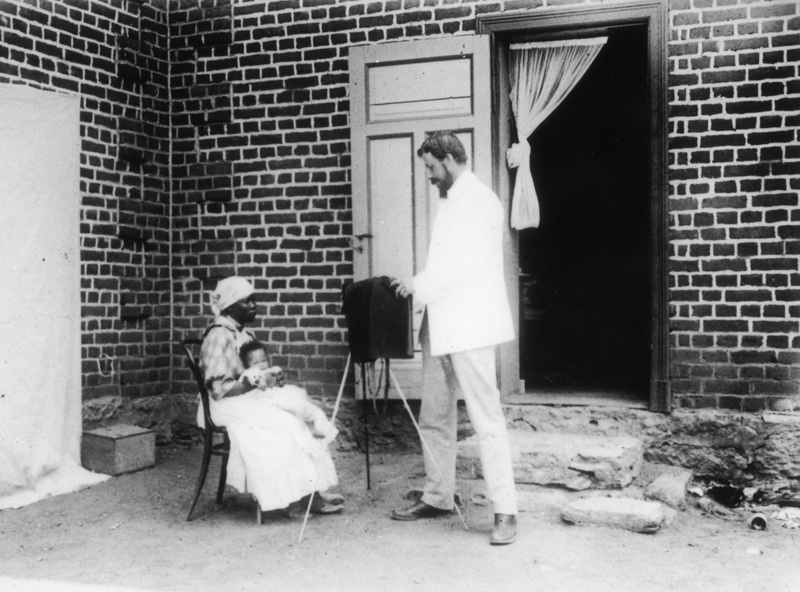

German South-West Africa and the “Rehoboth Basters”

Sources:

- Fischer, E. (1913). Die Rehobother Bastards und das Bastardierungsproblem beim Menschen. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- Hatlapa, R. (2007). 3.1.4 Ihnestrasse 22: Das Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Anthropologie, Menschliche Erblehre und Eugenik und Seine Mitarbeiter: Eugen Fischer. In J. Hoffmann, A. Megel, R. Parzer & H. Seidel (Eds.), Dahlemer Erinnerungsorte (170-183). Berlin: Franke & Timme.

- Lösch, Niels C. (1997). Rasse als Konstrukt: Leben und Werk Eugen Fischers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Rehoboth Basters: History. (2013). Retrieved Aug 6, 2013, from http://www.rehobothbasters.org/history.php

- Schaeuble, J. (1958). Eugen Fischer vor fünfzig Jahren in Rehoboth. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 49(2), 259.

Political Implications of the “Rehobother Basters” study

Eugen Fischer believed people of “mixed” background, who he referred to as “bastards” to be superior to purely indigenous peoples, yet still below the colonizers. He advocated for the “racial” segregation of society, wherein these people of “mixed” background should serve as overseers of the indigenous peoples, while being subservient to the colonists. His recommendation can be seen as a biological legitimization of apartheid. The so-called “bastard studies” continued at the KWI-A, although Fischer did not himself return to German South-West Africa. Instead he sent someone in his place to collect data from his original research subjects, the “Rehoboth Basters.” This vein of research also had a direct impact on the research direction of the KWI-A and on later policies of the Third Reich. For example, Fischer supervised a study conducted in 1939 on the “Rhineland bastards”, which led to the forced sterilization of hundreds of youth in Germany.

Sources:

- Fischer, E. (1913). Die Rehobother Bastards und das Bastardierungsproblem beim Menschen. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- Fischer, E. (1938). Neue Rehobother Bastardstudien. I. Antlitzveränderungen verschiedener Altersstufen bei Bastarden. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 37(2), 127-139.

- Lösch, N. (1997). Rasse als Konstrukt: Leben und Werk Eugen Fischers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

At the KWI-A

Eugen Fischer’s research, leadership within the German Society for Racial Hygiene, and publication of the Journal for Morphology and Anthropology led him to be called to Berlin to become the director the KWI-A. As director and along with his responsibilities as professor, research manager, and political advisor, Fischer found little time to complete his own research. However, through his leadership, the researchers and doctoral students at the institute refined and developed his research on “race” that had brought him acclaim with his “Rehoboth Basters” study in 1913.

After his resignation from the KWI-A, Fischer remained a respected member of the German anthropology community, publishing his memoirs, and continuing to act as a mentor to fellow anthropologists. He was never held responsible for his research and its consequences.

Sources:

- Lösch, N. (1997). Rasse als Konstrukt: Leben und Werk Eugen Fischers. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Schmuhl, H.-W. (2003). The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human heredity and Eugenics, 1927-1945. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (Vol. 259). Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag.

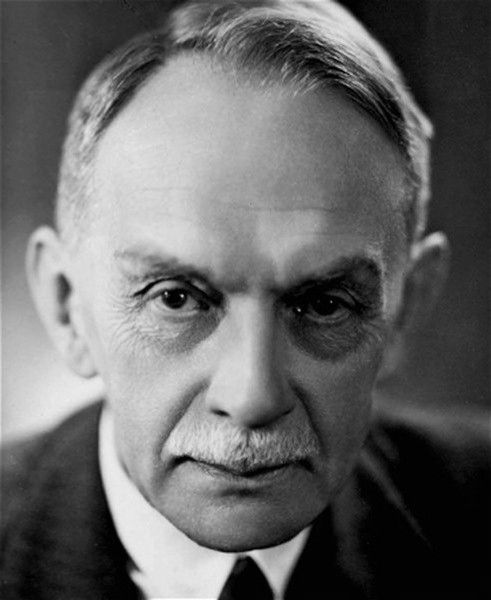

Fritz Lenz

(1887–1976)

Medical Researcher and Eugenicist

Director of the Department of Eugenics at the KWI-A (1933-1945)

Lenz was a eugenicist and a defender of mass sterilization. According to Lenz, eugenics was necessary to stop the rising “catastrophe” of the degeneration of the (Nordic) “race”. He considered racial mixing a danger to “racial purity”. In addition, one of the measures that Lenz politically advocated for was the sterilization of people with mental disabilities.

Lenz was a eugenicist and a defender of mass sterilization. According to Lenz, eugenics was necessary to stop the rising “catastrophe” of the degeneration of the (Nordic) “race”. He considered racial mixing a danger to “racial purity”. In addition, one of the measures that Lenz politically advocated for was the sterilization of people with mental disabilities.Fritz Lenz appreciated the centrality of eugenics in the Nazi party’s program. Indeed, much of the Nazi population policy was based on ideas developed and defended by Lenz and other eugenicists. Lenz praised Hitler’s enthusiastic appropriation of ideas from the book The Principles of Human Heredity and Race Hygiene published by Eugen Fischer, Erwin Bauer and Lenz himself. Lenz also shared Hitler’s concern about the perceived “racial mixing” taking place in France due to the immigration from the colonies.

After World War II, Lenz continued working as a professor for human genetics at the University of Göttingen.

“One can recognize a N------ [N-Word]⊗ with great certainty through his outer appearance, and one rightly assumes that he also has the mental and spiritual nature of a N----- [N-Word]⊗”(Fritz Lenz, 1942).

“Yes, there are Jews that have most of the outer characteristics of the Nordic race and yet are of Jewish nature” (Fritz Lenz, 1941).

“I have sympathy also for the chimpanzees and gorillas, and I'm very sorry that they are facing extinction like so many other species, and the so-called primitive peoples too. Also the fate that has befallen millions of Jews is very painful to me; but all this cannot determine that we should consider biological issues other than purely factually” (Fritz Lenz, 1951).

Sources:

- Klee, E. (2005). Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945 (2nd ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch, 366–367.

- Lenz, F. (1931). Die Stellung des Nationalsozialismus zur Rassenhygiene. Zeitschrift für die Erforschung des Wesens von Rasse und Gesellschaft und ihres gegenseitigen Verhältnisses, für die biologischen Bedingungen ihrer Erhaltung und Entwicklung, sowie für die grundlegenden Probleme der Entwicklungslehre, 25, 303.

- Lenz, F. (1934). Die Bedeutung der Rassenfrage für den praktischen Arzt (Vortrag gehalten im Ärztlichen Verein zu Hamburg am 19. VI. 1934). Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, 60(36), 1349.

- Lenz, F. (1941). Über Wege und Irrwege rassenkundlicher Untersuchungen. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 39(3), 397.

- Lenz, F. (1942). Noch einmal die Irrwege bei rassenkundlichen Untersuchungen. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, Erb- und Rassenbiologie, XL(1), 186.

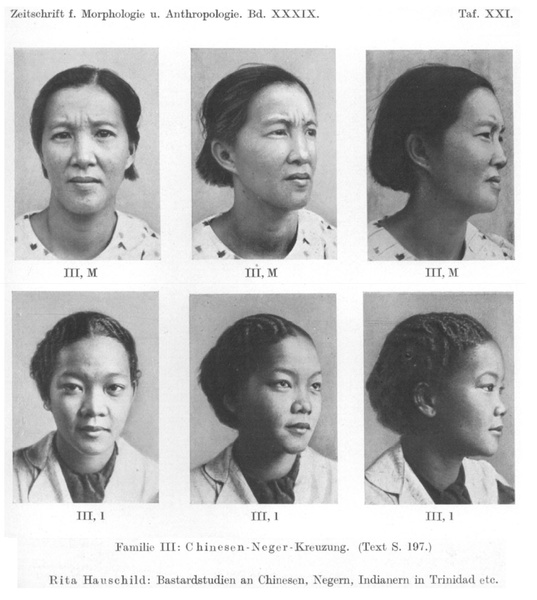

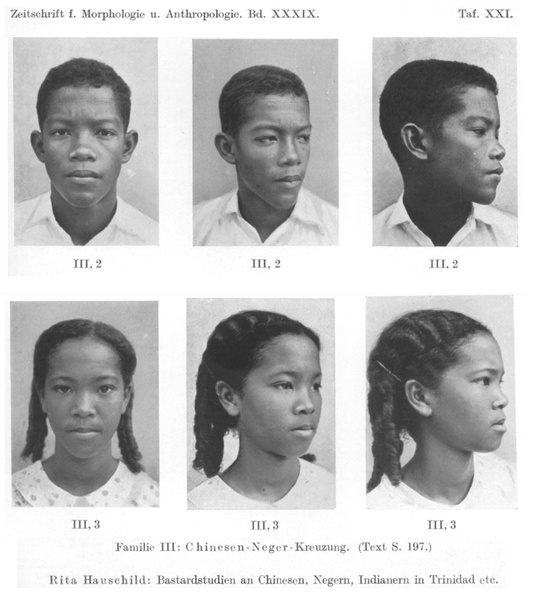

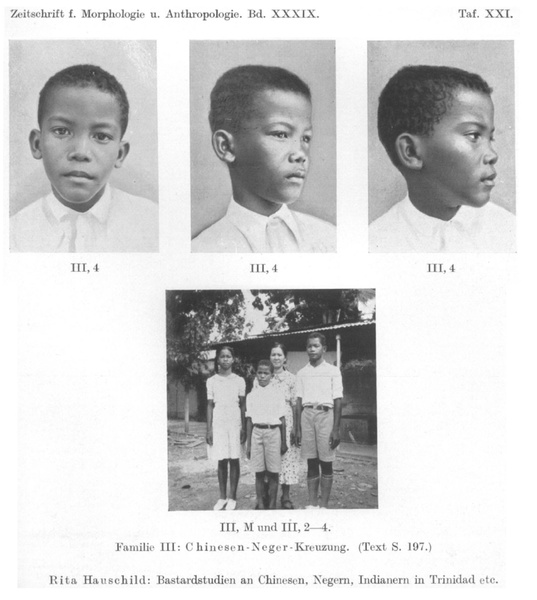

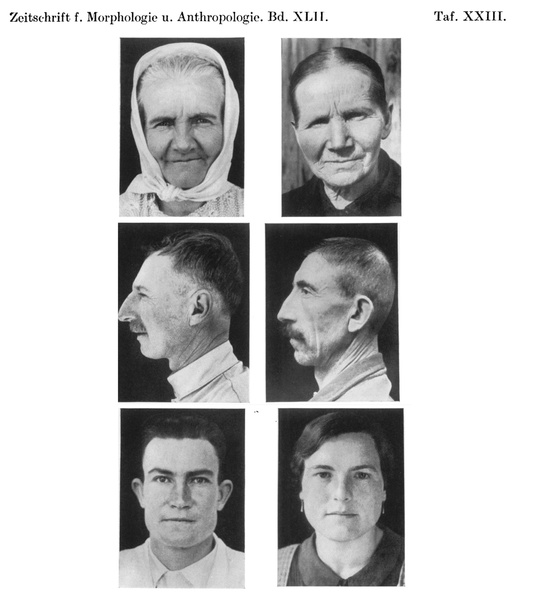

Rita Hauschild

(1912–1950)

Anthropologist and Medical Researcher

Researcher at the KWI-A

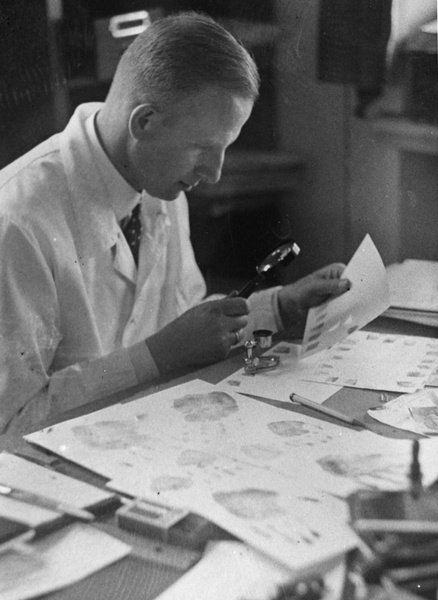

Under Fischer’s supervision, Rita Hauschild undertook research with three dead human embryos, concluding that “racial” differences could be perceived by the form of the skull of embryos.

In 1936-1937, she received the support of KWI-A to research “racial” mixing in Trinidad, where she catalogued physical features of different “interracial” families of Chinese, African, European and indigenous descent.

At the same time she went to Venezuela to research the German settlement Tovar, where she compared the skulls of the settlers to those of their relatives who had remained in Germany. Unlike her earlier studies, Rita Hauschild found that the form of the skulls bore no direct relation to racial differences or mental abilities. She considered this correlation weak, "much more than assumed before". However, Hauschild only published these findings after World War II, when the KWI-A was already closed.

Sources:

- Hauschild, R. (1937). Rassenunterschiede zwischen [n-------] und europiden Primordialcranien des 3. Fetalmonats: Ein Beitrag zur Entstehung der Schädelform. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 36(2), 215-280.

- Hauschild, R. (1941). Bastardstudien an Chinesen, [N-----], Indianern in Trinidad und Venezuela. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 39(2), 181-289.

- Hauschild, R. (1939). Rassenkreuzungen zwischen [N-----] und Chinesen auf Trinidad. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 38(1), 67-71.

- Haushild, R. (1950) “Colonia Tovar, Eine anthropologische Vergleichsuntersuchung zwischen einer badischen Siedlung in Venezuela und ihren Heimatdörfern.” Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 42(2), 262.

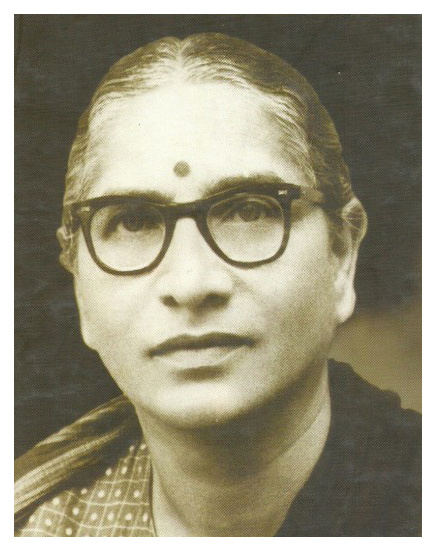

Irawati Karvé

(1905-1970)

Anthropologist

Doctoral Student at the KWI-A (1928-1930)

“I, Irawati Karvé, neé Karmarkar, was born on 12.15.1905 in Myinggan (Burma) ... I came to Berlin in September 1928 and was matriculated at the University of Berlin.”

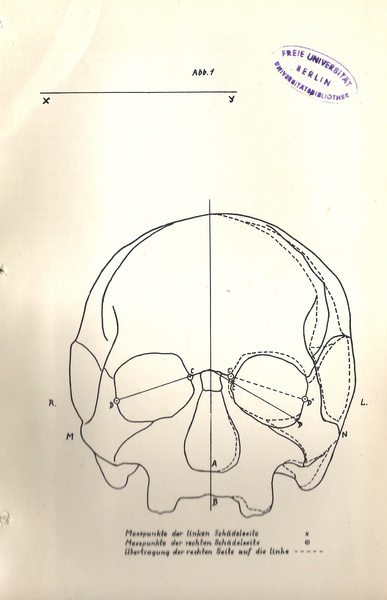

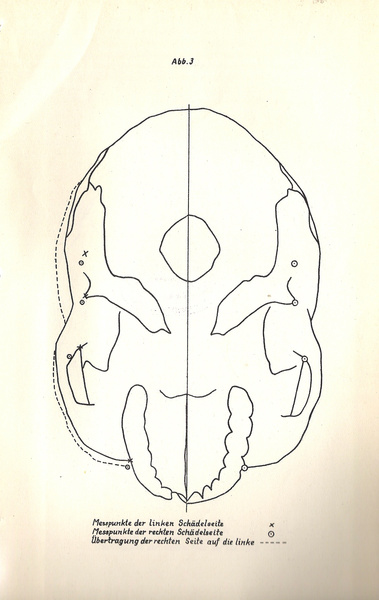

For her dissertation, Irawati Karvé was instructed by Fischer to research skulls and determine whether “1. differences in the right and left [skull] asymmetry exist and 2. differences in the frequency of occurrence of these asymmetries exist in different races, specifically European and other races.” She went about this task by researching skulls from around the world, which had been taken from various colonies and kept in the KWI-A and other European skull collections. Her findings, specifically regarding “race”, stated the opposite of what her colleagues at the KWI-A had previously found. Karvé concluded that differences in the skulls between any races do not exist.

⊗ We refuse to reproduce the original words due to their racist and demeaning intent.

Sources:

- Karvé, I. (1931). Normale Asymmetrie des menschlichen Schädels: Inaugural-Dissertation. (Doctoral Disertation). Leipzig: Schwarzenberg & Schumann.

- Sundar, N. (2007). “In the cause of anthropology: the life and work of Irawati Karve.” In P. Uberoi, S. Deshpande and N.Sundar (Eds.), Anthropology in the East. Leipzig: Schwarzenberg & Schumann, 373.

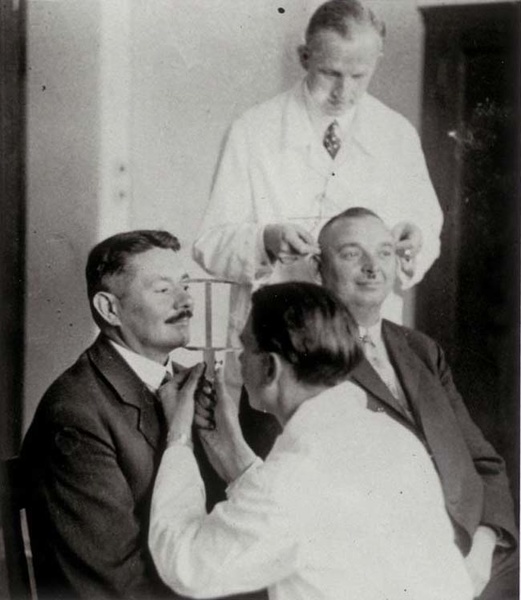

Wolfgang Abel

(1905-1997)

Zoologist and Anthropologist

Research Assistant at the KWI-A (1931-1941)

Director of “Race” Studies at the KWI-A (1941-1945)

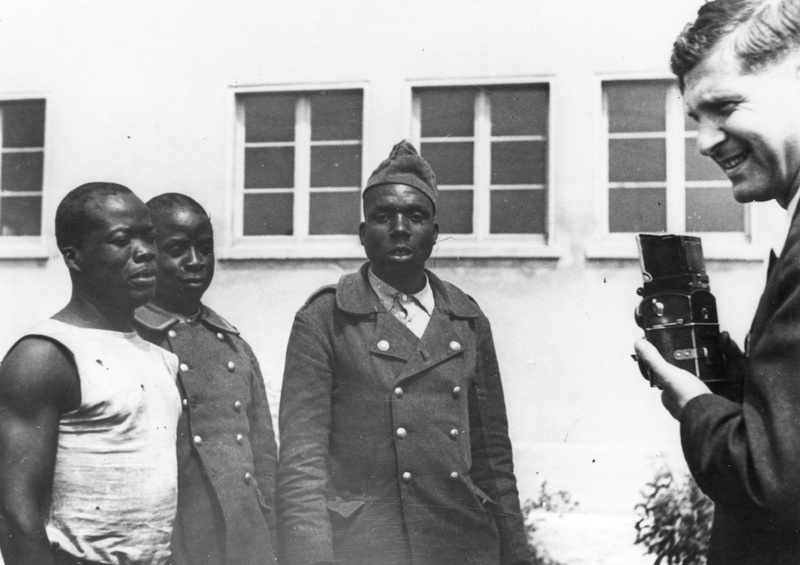

Joining the KWI-A in 1931, the anthropologist Wolfgang Abel was the only other researcher besides Fischer at the institute who had spent considerable time studying the effects of “racial mixing”. Therefore, when in 1933 the German government called upon Fischer to research the “Rhineland bastards”, he sent Abel in his place. These were children in the Rhineland born of German mothers and French colonial soldiers, who had fought in World War I and were referred to in Germany as the “black danger”. Like Fischer’s studies published in 1913, Abel too believed that these children were superior to their Black fathers, yet beneath their white German mothers, and must for this reason be prevented from reproducing. The consequence of his research and recommendations was the forcible (and illegal) sterilization of 385 of these youth.

Sources:

- Campt, T. (2004). Other Germans: Black Germans and the politics of race, gender, and memory in the Third Reich. University of Michigan: Michigan.

- Schmuhl, H.-W. (2003). “The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human heredity and Eugenics, 1927-1945.” In Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science (Vol. 259). Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag.

- Wolfgang, A. (1937). Über Europäer-Marokkaner-und Europäer-Annamiten-Kreuzungen. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und Anthropologie, 36(2), 311-329.

- Wolfgang, A. (1934). Bastarde am Rhein. Neues Volk. Blätter des Rassenpolitischen Amtes der NSDAP, (2), 4-6.

Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer

(1896–1969)

Medical Researcher

Director of the Department of Human Heredity

at the KWI-A (1927-1935)

Director of the KWI-A (1942-1945)

Von Verschuer was a pioneer in twin research. From 1943 onwards, he mentored his pupil Josef Mengele, who was serving as a doctor in Auschwitz. There, Mengele undertook various medical experiments, in particular twin experiments, with living prisoners of the concentration camp. He also sent human remains, such as the eyes of murdered prisoners, from Auschwitz to Berlin for research at the KWI-A.

From 1951 on, von Verschuer was professor at the University of Münster, where he established and directed the Institute of Human Genetics. During his lifetime, von Verschuer never faced negative consequences for his work during the Nazi period - his actions remained unpunished.

“[Whether] N----- [N-Word] ⊗, G------ [Roma and Sinti]⊗, Mongols [sic], South Sea Islander or Jews - hybridization of a foreign race in a people leads to change of the biologic condition that corresponds to the biologic characteristic of that people and from which its particular culture originates.” (Von Verschuer, 1937)⊗ We are refusing to reproduce the original words due to their racist and demeaning intent.

“If [the genetic disposition] is a fate, let us be the master of that fate, facing the genes as a task that is posed to us!” (Von Verschuer in different texts and speeches)

“The purity of race was one of the principles of life. I was raised by my parents with this natural approach. […]. The separation of races and people, between Germans and Jews, was, for me, necessary and the optimal solution […] for both parties. Through my scientific work, I strove to develop a basis for a solution of this issue.” (Von Verschuer, in autobiographical notes written by the end of the war in 1945)

Sources:

- Von Verschuer, O. (1933). Das Erb-Umweltproblem beim Menschen. Forschungen und Fortschritte. Nachrichtenblatt der Deutschen Wissenschaft und Technik, 9, 54-55.

- Von Verschuer, O. (1936). Rassenhygiene als Wissenschaft und Staatsaufgabe. In Frankfurter Akademische Reden (Vol. 7). Frankfurt: Bechhold.

Von Verschuer, O. (1937). Die Rasse als biologische Größe. In W. Rünneth (Ed.), Die Nation vor Gott. Zur Botschaft der Kriche im Dritten Reich. Berlin: Wirchen Verlag: Berlin.[s] - Von Verschuer, O. (1943). Bevölkerungs- und Rassenfragen in Europa. Warnende Beispiele: Frankreich und Schweden. Qualitative Bevölkerungszunahme erforderlich. Wissenschaft und Hochschule – Berichte aus allen Gebieten des wissenschaftlichen Lebens, 549.

- Von Verschuer, O. (1993). Was kann der Historiker, der Genealoge und der Statistiker zur Erforschunp. g des biologischen Problems der Judenfrage beitragen? (Anm. 39), 218-222. Cited in Weß, Ludger. Humangenetik zwischen Wissenschaft und Rassenideologie: Das Beispiel Otmar von Verschuer (1896-1969). In Wohlleben, T. & Linne, K. Patient Geschichte (179). Frankfurt am Main: Zweitausendeins.

- Von Verschuer, O. (2003). Mein wissenschatlicher Weg. In E. Henning (Ed.), Dahlemer Archivgespräche (Vol. 9). Berlin: Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft.