The Institute

Ihnestraße 22

The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for

Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics (KWI-A)

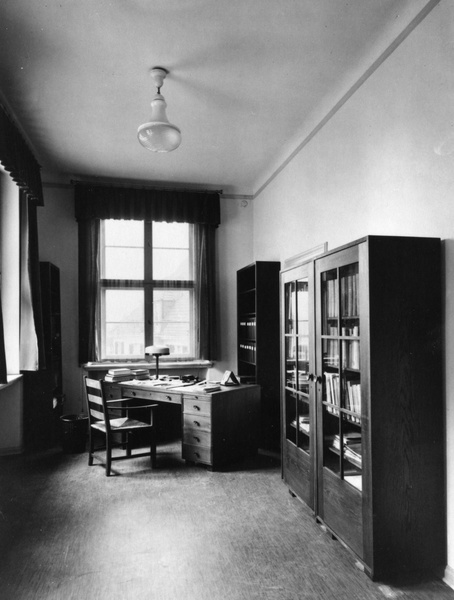

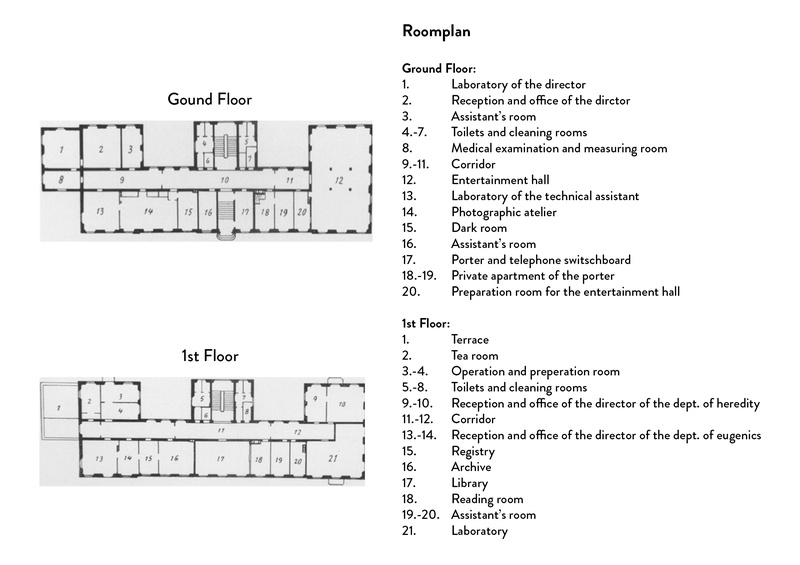

Founded in September 1927, the KWI-A was a leading German research institute in the areas of anthropology, human heredity, and eugenics. The institute was housed in the building at Ihnestraße 22, presently home of the Otto Suhr Institute for Political Science of the Free University of Berlin. The KWI-A was one of 59 institutes and research sites of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science, which provided research in a variety of disciplines from 1911 to 1945. The KWI-A was funded by state subsidies, grants from research foundations, and private investors, including the Rockefeller Foundation. The eugenicist and former Jesuit Hermann Muckermann also played an important role in the financing of the institute through the fundraising tours he undertook, raising money for the institute from his contacts in the Catholic Church. The purpose of the institute was closely linked to politics as it sought to raise the social welfare of the state through scientifically guided population policy. Divided into three departments - anthropology, human heredity, and eugenics -, the sections collaborated to produce a body of research that provided scientific legitimacy for the concept of “race”. The work of the institute included scientific research, teaching, and supervision of doctoral students, many of whom had come from abroad. It was this research that would later be used to legitimize sterilization programs as well as genocide.

At the beginning of 1944 work at the institute became increasingly difficult

with damage to the institute's building resulting from air raids, and the

institute’s work was relocated outside of Berlin. At the request of institute

director Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer numerous files were also destroyed so as

to prevent them from falling into “enemy hands”. Von Verschuer had hoped to

reopen the institute after the end of the war. However, as the extent to which

the institute and its members, especially von Verschuer, were involved in the

crimes of the National Socialists became clear, it was not reopened. Despite

this, the institute was never officially dissolved and the researchers were

able to continue their work at other research institutions. The Kaiser Wilhelm

Society itself was renamed the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of

Science in 1948.

Sources:

- Brocke, B. & Laitko, H. (1996). Die

Kaiser-Wilhelm-/Max-Planck-Gesellschaft und ihre Institute: Studien zu ihrer

Geschichte: Das Harnack-Prinzip. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Fischer, E. (1928). Das Kaiser-Wilhelms-Institut für Anthropologie,

menschliche Erblehre und Eugenik. Zeitschrift für Morphologie und

Anthropologie, 27(1), 147-152.

- Schmuhl, H.-W. (2008). Crossing Boundaries: The Kaiser Wilhelm

Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, 1927-1945.

Berlin: Springer.

The Skull Collection

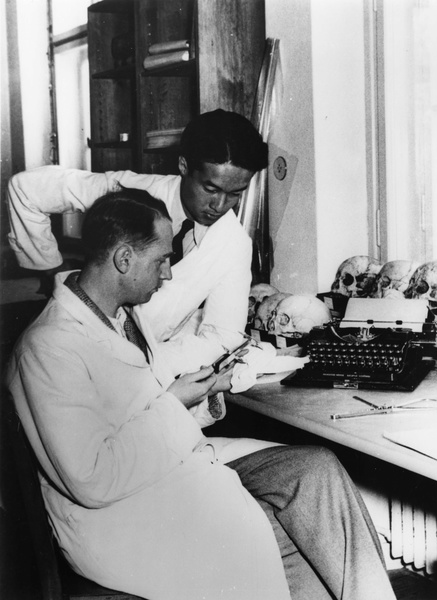

The collection of various “anthropological research materials” - mostly

human bone remains - from colonized territories was widespread during the late

19th and early 20th century. Numerous institutes and museums in Germany and

across the world housed such collections, which were often used for

anthropometric research. The attic of the KWI-A building at Ihnestraße 22

housed a skull and skeleton collection of around 4,000 to 5,000 individual

pieces. The collection, known as the “S-Sammlung”, was started by

anthropologist Felix von Luschan, who worked at what is today the Ethnological

Museum of Berlin at the end of the 19th century. Thereafter it was moved to the

Friedrich Wilhelm University (renamed Humboldt University of Berlin in 1949)

before being loaned to the KWI-A in 1928. Anthropologist and schoolteacher Hans

Weinert was given the task of organizing and compiling the collection.

The collection contained skulls and other human remains from former German colonies in Africa and Southeast Asia, as well as from numerous other locations across the world. Remains of genocide victims from the Shark Island Concentration Camp in Namibia were also sent to Berlin, and the S-Sammlung contained at least 30 Namibian skulls obtained during German colonial rule. Prior to becoming KWI-A director, Eugen Fischer himself had dug up Khoikhoi graves during his time in German South-West Africa to bring back to the University of Freiburg. This act was made possible by the genocide’s decimation of the Khoikhoi population.

Many researchers benefited directly from colonialism, as it enabled them to obtain objects for their research, as well as conduct research in the colonies. Although some repatriations have occurred, the process of restitution is still on-going and human remains from the former German colonies are still found in Berlin and across Germany today. To this day Herero and Nama representatives, along with other groups, demand the repatriation of the remains of their people.

Sources:

- Bergmann, A., Czarnowski, G. & Ehmann, A. (1989). Menschen als Objekte

humangenitischer Forschung und Politik im 20. Jahrhundert. In Pross,

Christian, & Aly, Götz (Eds.), Der Wert des Menschen: Medizin in

Deutschland 1918-1945 (121-142). Berlin: Edition Henrich Berlin.

- “Jahresbericht, 1927-28”. (1928) Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, Abt.

I, Rep. 3, Nr. 3.

- “Personalakte Hans Weinert”. (1928) Archiv der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft,

Abt. I, Rep. 3, Nr. 31.

- Stoecker, H. (2012). Post vom Feldlazarett: Namibische Schädel in Berliner

anthropologischen Sammlungen. iz3w, (331), 32-33.

- Stoecker, H. (2013). “Knochen im Depot: Namibische Schädel in

anthropologischen Sammlungen aus der Kolonialzeit,” in J. Zimmerer (Ed).

Kein Platz an der Sonne. Erinnerungsorte der deutschen

Kolonialgeschichte. Frankfurt am Main: Campus.